Why is it that a few pounds of metal and vinyl can obscure a person’s attractiveness?

Why is it that a few pounds of metal and vinyl can obscure a person’s attractiveness?

Up until two years ago, I thought I had the vanity issue under control. Like many women of my generation, I believed that how I looked was not the most important thing about me. Although I paid attention to my hair and nails and makeup and hemlines, I wasn’t obsessive about them. Far more effort was expended on my personal and professional ambitions and commitments. It never occurred to me that a day would come when my appearance would outweigh my accomplishments or my personality. But, then, it never occurred to me who jogged and danced and rode horses that I would one day be confined to a wheelchair. I was never one of those little girls who got lots of attention because they were so pretty or cute. In fact, I can count on one hand the total number of times my parents commented on how I looked. The messages of my youth, instead of being centered on appearance, were focused on performance. Music lessons honor rolls, and horse shows were the tools I used to build my self-esteem. As I grew, my family continued to regard how I looked as (a) an accident of genetics and (b) a frivolous concern. It wasn’t until I went away to college that I discovered the age-old pleasure that women have found in making the most of what nature has given them. Looking as good as possible became a sort of joyful challenge. And while I never developed into a cosmetics-counter junkie, I did grow into a woman who could look into a mirror and be pleased at what looked back at me. Makeup, clothes, and jewelry became as essential to my peace of mind as my piano and my passport.

By the time I celebrated my thirtieth birthday, I’d discovered that being your best was a goal large enough to include looks as well as achievements. And, because I had had a vanity-free youth, I derived special pleasure whenever friends or colleagues would say “nice blouse” or “I like your nail polish” or any of the countless quotidian compliments people routinely give one another. It didn’t bother me that I wasn’t a natural beauty. I was more than happy to expend the time, effort, and attention to detail

it took to be my best. But then, two years ago, the secret pleasures I derived from “looking good” evaporated.

That’s when a neurological disorder attacked my legs and I was forced to view life from a wheelchair. Once I came to terms with my limited mobility, I was struck not so much by how the wheelchair changed my view of life but by how much the wheelchair affected the way I was viewed by others. Men rarely even look at a limited mobility, I was struck not so much by how the wheelchair changed my view of life but by how much the wheelchair affected the way I was viewed by others. Men rarely even look at a woman who is in a wheelchair. The only way to regain a semblance of visibility is to move into a “regular” chair when at a restaurant or social function and make sure that the wheelchair is placed well out of sight. The evaporation of my (however limited) visual appeal came as an unwelcome additional burden to my, already up‑ setting disability.

Stubbornness, however, ensured that—even if no one else was able to—I was determined to continue to see myself as I’d always been. I still agonize over my accessories, I insist on dressing as nicely as possible under the circumstances, and I continue to worry about my weight. If anything, my wheelchair restricted existence has taught me that appearance—in our society, at least—is far more important than I realized. My inner voice insists that it’s the same me as before, with the only change being that my legs simply don’t work these days. My face isn’t covered with warts, my teeth haven’t turned green, and my sense of humor is intact. But often, when the wheelchair comes into view, people can’t see the manicure or the makeup. They never even have a chance to discover what my personality might be like because they bring their own uncomfortable prejudices to our encounters.

Whereas I once had vanity concerns that focused on finding the right color of nail polish and tracking down the perfect pair of shoes, these days my constant battle is one of stabilizing my self-esteem. It takes a great deal of energy to rise above the insensitivity of able-bodied people who are unable to see that the occupant of a wheelchair is, first and foremost, a fellow human being and deserves to be treated with a modicum of dignity, regardless of whether the disability is visible or hidden.

For the handicapped, by definition, belong to a crapshoot, a nonrestrictive club. The person who looks away when I approach, or who automatically assumes that my mental skills are diminished because my legs aren’t functional, may wake up someday and find himself or herself—like me—an unwilling member of America’s least enviable organization.

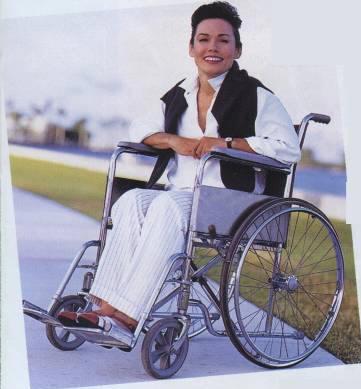

Occasionally, on TV, we get to see an attractive woman in a wheelchair. (I particularly identified with the brunet lawyer in last year’s Equal Justice.) But when it comes to the rest of the media, it seems as if only Vietnam vets, the aged, and the terminally ill are entitled to be wheelchair dependent. Well, here’s a news flash: There are lots of pleasant, attractive women whose lives—while they may have been altered by accident or illness—are far from over. We are struggling to make the best of our current situation and to look as good as possible instead of succumbing to the seductive “Why bother?” blahs.

It’s hard enough in today’s fashion-model, glamour-obsessed world for an ordinary woman to feel pretty. I’ve faced the challenges of cellulite, the errant gray hair, introductory crow’s feet, dry skin, and peeling fingernails with equanimity. But when faced with the wicked witch, pretty-robbing power of the wheelchair, it’s hard not to feel that I may have met my match.